BRAINS IN BRIEFS

Scroll down to see new briefs about recent scientific publications by neuroscience graduate students at the University of Pennsylvania. Or search for your interests by key terms below (i.e. sleep, Alzheimer’s, autism).

Adolescent nicotine exposure fundamentally changes the brain to make subsequent morphine use in adulthood more rewarding

or technically,

Paradoxical Ventral Tegmental Area GABA Signaling Drives Enhanced Morphine Reward After Adolescent Nicotine

[See original abstract on Pubmed]

Dr. Ruthie E. Wittenberg was the lead author on this study. Ruthie is currently a postdoc in the lab of Paul Kenny at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Her research is focused on the intersection of cellular immunology and addiction neuroscience. In the future, she hopes to establish an independent academic research career studying the neurobiology of substance use disorders and motivated behaviors.

or technically,

Paradoxical Ventral Tegmental Area GABA Signaling Drives Enhanced Morphine Reward After Adolescent Nicotine

[See Original Abstract on Pubmed]

Authors of the study: Ruthie E. Wittenberg, Sanghee Yun, Kechun Yang, Olivia K. Swanson, Shannon L. Wolfman, Lorianna M. Colón, Amelia J. Eisch, and John A. Dani

In the United States, drug overdose is a leading cause of death, and most drug overdoses involve the use of opioids. Opioids (sometimes called narcotics) are often medically prescribed for treating chronic pain. However, opioids, whether prescribed or not, have high abuse risk, and taking them can lead to opioid use disorder (OUD). OUD is a type of substance use disorder or addiction that involves a “problematic pattern of opioid use that causes significant impairment or distress” according to the CDC. Anyone can become addicted to opioids, but some things might make it more likely for someone to develop OUD. For example, adolescent nicotine use is a risk factor for developing OUD later in life. Most tobacco use begins during adolescence, with teens vaping or using nicotine pouches.

The link between early-life nicotine use and OUD is not well understood, so for her PhD in the labs of John Dani and Amelia Eisch, former NGG student Ruthie Wittenberg wanted to understand how nicotine use during adolescence could change the brain to promote morphine reward in adulthood.

Adolescence is the time in development when the brain is more flexible and with greater plasticity than in adulthood. One such part of the brain, the ventral tegmental area (VTA), is considered to be the start of the main reward pathway. Increased neuronal activity, altered dopamine signaling, and structural changes are examples that all contribute to increased reward sensitivity. Evidence from both human and animal studies indicate that using drugs during adolescence, when the brain is most flexible, can create long-lasting changes in the brain and in behavior that can extend into adulthood.

To understand how adolescent nicotine exposure changes reward-related behaviors in adulthood, Ruthie gave adolescent mice nicotine for 2 weeks and waited until they were older to see how they responded to opioids, like morphine. She wanted to see how adult mice who had been exposed to nicotine earlier in life responded to the rewarding properties of opioids compared to mice who had never been exposed to nicotine. Ruthie used a conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm in mice to test reward learning. CPP works like this: there are different chambers or “contexts.” They differ in both visual and tactile cues. Each context has a different pattern of stripes or colors on the wall to help the mice be able to tell the difference between the chambers. The floor of each chamber also differs (e.g. they have distinct ridges or grooves), providing a tactile cue.

In this case, mice received morphine in one chamber, and a control drug (saline) in another chamber for 3 days. After the 3 days, Ruthie allowed the mice to move freely between the chambers and measured how much time they spent in the morphine-paired chamber compared to the saline-paired chamber. If mice spent more time in the reward chamber than the saline chamber, this indicated they were able to associate that context with the reward (the opioid), and that they remembered that this chamber felt more rewarding. Ruthie tested the mice who had been previously exposed to nicotine and mice who had never been given nicotine in the morphine CPP test, and she found that mice that had been exposed to nicotine spent more time in the morphine chamber than the group of mice that never had nicotine. The non-nicotine group still remembered the chamber where they got morphine but they spent significantly less time there than the nicotine group. In conclusion, Ruthie found that morphine was even more rewarding to the nicotine-exposed mice than the mice who were never exposed to nicotine.

Ruthie further explored what changes in the brain are happening because of adolescent nicotine use to make this behavior happen?

To understand the link between using nicotine in adolescence and morphine later in adulthood, Ruthie looked at the VTA, the origin of the reward pathway. The VTA is made up of neurons that release one or more neurotransmitters to communicate with each other. It is also well-known for producing dopamine, which motivates the seeking of drugs and other rewards. Additionally, the VTA releases other neurotransmitters, like GABA, which helps to quiet other neurons, like those that release dopamine. Since the brain is really flexible in adolescence, Ruthie wanted to know if changes in VTA GABA neurons could be a link between nicotine use in adolescence and morphine use in adulthood.

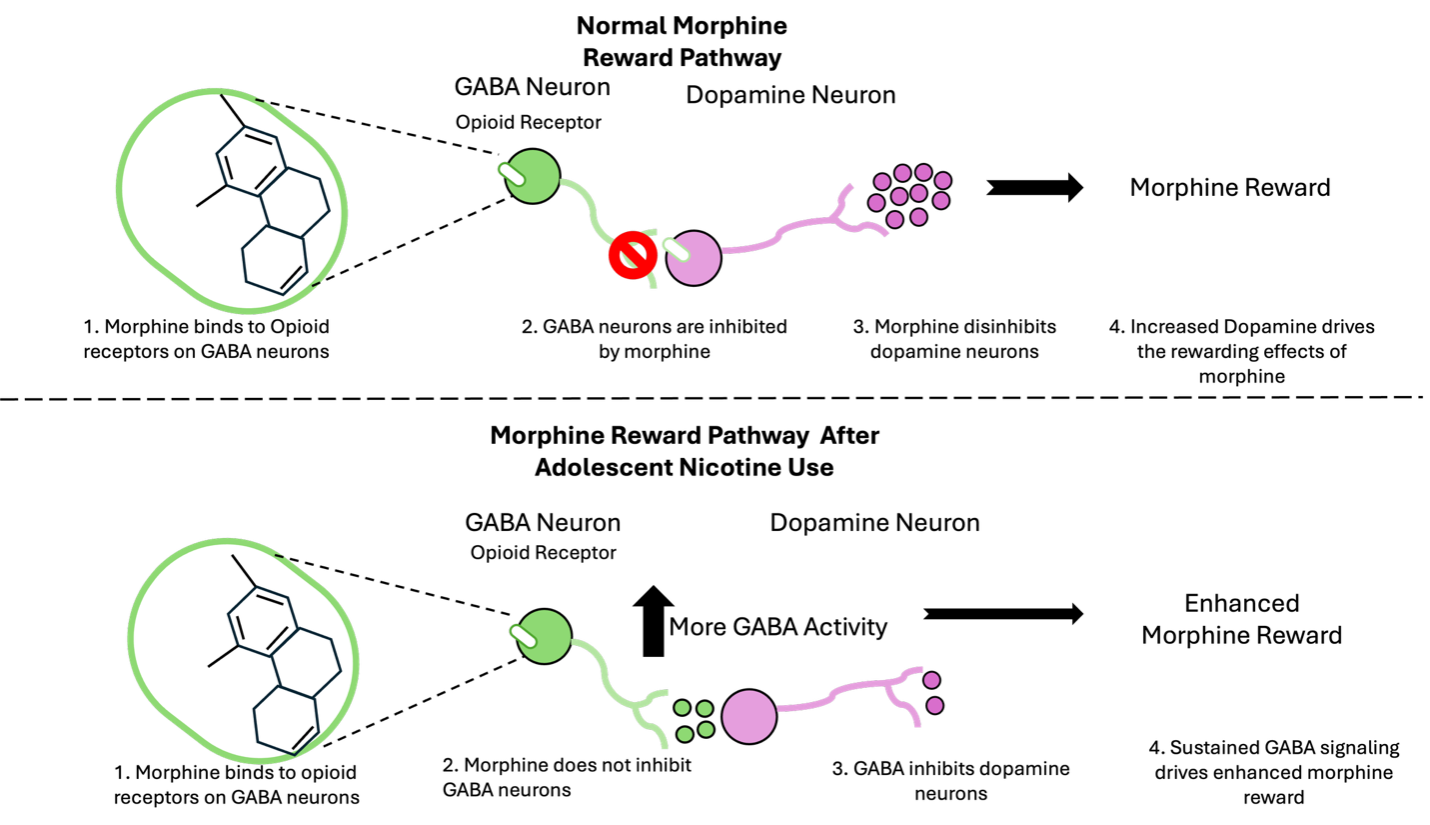

Chronically using nicotine in adolescence changes how VTA GABA neurons communicate with other neurons. Ruthie wanted to know how adolescent nicotine use changes how VTA GABA neurons respond to morphine in adulthood. As a result, she used patch-clamp electrophysiology to record the electrical activity of these neurons. An important thing to note is that opioids like morphine bind to endogenous opioid receptors, meaning receptors mice already have on their VTA GABA neurons. When morphine acts on these receptors, it inhibits neural activity. Moreover, GABA neurons quiet the VTA dopamine neurons and morphine quiets GABA neurons, allowing dopamine neurons to release more dopamine, leading to the rewarding effects of morphine. This process is called disinhibition, where the neurons that inhibit (GABA neurons) are inhibited themselves, which allows other neurons to start to fire.

Figure 1: Schematic representation of how the VTA reward circuit is fundamentally altered after adolescent nicotine use.

Ruthie found that adolescent nicotine use changed the way that this neural circuit was acting, such that morphine no longer disinhibits dopamine neurons (Figure 1). By recording from GABA and dopamine neurons in the VTA in adult mice, she found that among mice exposed to nicotine as adolescents, morphine no longer inhibited GABA neurons and it also did not change how dopamine neurons fired.

Ruthie’s results would suggest that sustained GABA neuron activity seemed to be driving the increased reward behavior seen in the CPP experiment. To test this, Ruthie artificially inhibited VTA GABA neurons in mice that had nicotine exposure during adolescence (enabling the VTA GABA cells of the nicotine animals to act like those of the water animals) and observed that the enhanced reward learning previously seen was blocked.

In conclusion, Ruthie determined that the VTA circuit is fundamentally changed after adolescent nicotine exposure. After adolescent nicotine use, VTA GABA neurons are no longer inhibited by morphine and additionally, mice find morphine more rewarding than normal. These findings challenge the canonical view of the brain’s reward system and advance our understanding of the mechanisms driving addiction-related behaviors. This may explain why prior drug exposure can make it more likely that people develop disorders like OUD. Great job Ruthie!

About the brief writer: Lucas Tittle

Lucas Tittle is a PhD Candidate in the labs of Dr. Guillaume de Lartigue and Dr. Kevin Bolding. His research is at the intersection of the olfactory system and gut-brain axis, and how external signals like odors and internal signals interact to change feeding behavior.