Engineering a Neuron Highway: A New Approach to Brain Repair

Dr. Erin Purvis Conway was the lead author on this study. Erin is a Civic Science Fellow at the Center for the Neurobiology of Learning and Memory and the NeuroEngage Lab at UC Irvine. Erin's career lies at the intersection of neuroscience and community engagement. She works to strengthen mutually beneficial partnerships and programs between UC Irvine and the local community.

or technically,

A three-dimensional tissue-engineered rostral migratory stream as an in vitro platform for subventricular zone-derived cell migration

[See Original Abstract on Pubmed]

Authors of the study: Erin M Purvis, Andres D Garcia-Epelboim, Elizabeth N Krizman, John C O’Donnell, D Kacy Cullen

You’ve heard it before from a parent or a concerned friend: “Make sure you wear a helmet!” But why are brain injuries often so much more devastating than injuries elsewhere in the body? One major reason is that the brain has a limited ability to heal. If you scrape your skin, the tissue regenerates. If you break a bone, it can be reset and will mend over time. Even the liver can regrow after substantial damage. But the brain is different. Neurons—the brain’s functional cells—are primarily generated during a short developmental window early in embryonic development, roughly between 3 and 16 weeks after conception. After that, neurogenesis, or the birth of new neurons, essentially halts in most regions of the brain. As a result, injuries that kill neurons often cause permanent, lasting deficits impacting cognition, emotional regulation, and personality.

However, there are some exceptions. Two brain regions are thought to continue to facilitate neurogenesis in mammals well into adulthood: the Dentate Gyrus and the Subventricular Zone (SVZ). It’s unclear why these brain areas maintain the capacity for neural production into adulthood. One hypothesis is that these brain areas play an important role in adaptive processes like memory and sensation which might require new neurons to help integrate new information.

In rodents, the newborn neurons from the SVZ can be transported to nearby brain regions by what can be imagined as a neuron highway. From the SVZ newborn neurons can be transported to the olfactory bulbs, which are responsible for processing smells in mice and rats, via the rostral migratory stream or RMS. Then in the olfactory bulbs the neurons can be put to work by making connections with existing neurons in the area. In adult humans, however, there is controversial evidence about whether a similar long-distance neuron migration pathway exists. While it is known that the adult human brain maintains an active SVZ, the existence and structure of the adult human RMS is disputed.

What if we could engineer an RMS and place it in the human brain, spanning from the SVZ to an area of injury and thus giving newborn neurons a direct route to injured areas where repair is needed? This could have wide-ranging applications in any disease or injury that results in a loss of neurons including traumatic brain injuries or neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson's disease.

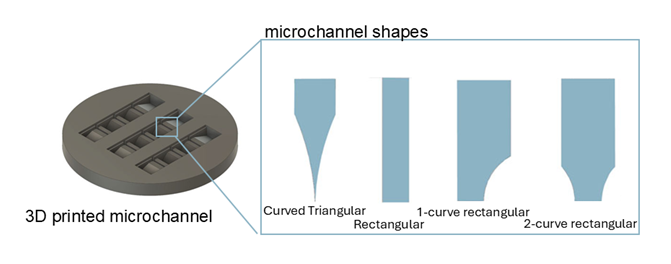

In Dr. Kacy Cullen’s lab at the University of Pennsylvania, Dr. Erin Purvis Conway and colleagues previously bioengineered a highway for neurons that functions similarly to the brain's RMS. They called it the tissue-engineered RMS or TE-RMS. This “living scaffold” mimics the RMS in your brain in several key ways. First, the scaffold is made of glia which are non-neuronal cells that play key roles in the brain alongside neurons. Second, the scaffold is three-dimensional and has a tube-like structure. Because the TE-RMS closely mimics the natural RMS, it can be engineered by combining glial cells with 3D-printed microchannels that guide their growth, along with the structural support and nutrients required for cell survival, allowing the structure to self-assemble. One major issue was that the number of TE-RMSs that formed properly were relatively low.

For the TE-RMS to have any chance of reaching the clinic where it can treat patients, it must be optimized to be reliable, reproducible, and robust. Erin’s goal for this study was to develop a method to build the highest number and most robust TE-RMSs possible. To optimize this process, Erin focused on the microchannels which are the foundation for forming the TE-RMSs. Erin developed several 3D printed microchannels of various shapes for the TE-RMSs to grow on: curved triangular, rectangular, 1-curve rectangular, and 2-curve rectangular. After factoring both the quality and quantity of TE-RMS’s produced, Erin determined the rectangular molds were best suited for this pipeline. Finally, Erin and her colleagues determined that the TE-RMS was functional. Over 14 days the newborn neurons migrated across the TE-RMS proving efficacy of the engineered scaffold outside the brain.

Figure 1:

Illustration of different possible microchannel shapes. Rectangular proved to be the best.

While a therapy based on this work is still far in the future, progress happens through careful, incremental steps like this one. By making TE-RMS structures easier and more reliable to build, Erin and her colleagues have improved a tool that helps scientists ask better questions about how the brain might someday be able to heal itself after injury or disease.

About the brief writer: Emily Pickup

Emily is a 6th year PhD candidate in Dr. Franz Weber’s lab. She is interested in the biological functions of sleep. Specifically, she is interested in understanding the function of REM sleep-specific p-waves.